By the time one enters La Luz de Jesus gallery, the vibe has been thoroughly set. The gallery itself is located inside a huge, eclectic gift shop called Soap Plant/Wacko — selling kitschy art, vintage toys, taxidermy and occult reference guides. The building’s exterior features an angular, geometric mural with two huge eyes gazing placidly over Hollywood Boulevard. Yet even with that priming, some of the work in the gallery this month may shock guests.

There are portraits of monsters rendered in photorealistic detail, their stretched smiles showing rows of gore-slicked teeth. Characters from children’s cartoons drink, smoke and fornicate with glee. There is one painting that looks like a plumbing diagram from across the room. Closer inspection reveals a bilious sheen on the pipes and junctions, showing them for the human organs they are. Multiple artists have incorporated walking, talking genitalia into their images.

“There’s some work in here that’s grotesque, for sure,” said Matthew Gardocki, curator and director of La Luz de Jesus. “Suggestive as well, but that’s what we do.”

Since it began in 1986, La Luz de Jesus has been at the forefront of the lowbrow art movement in Los Angeles. Lowbrow is an expansive term. It includes work that resists classical concepts of beauty, focusing more on the expressive, the bizarre and the grotesque.

Lowbrow freely incorporates pop culture references, humor and play. Much inspiration comes from the fringes of the mainstream art world: comics, graffiti, tattooing, surf and skate graphics, punk show flyers, heavy metal album covers, movies posters, commercials and folk art.

“Everything But The Kitchen Sync” is the gallery’s annual juried exhibition. Gardocki sifted through about 900 submissions to pick the 243 artworks by 103 artists in this year’s show.

“I’m always looking at work and I’ve been doing it for so long that it’s just whatever clicks with me,” said Gardocki. “It’s not necessary that it has to be political. It’s just how I react to it when I see it. And that’s usually how I go through the submissions, it’s a yes/no thing very quickly. It’s the way I work, it’s being around artwork all the time my whole life.”

Given lowbrow’s rejection of universal standards of beauty, it stands to reason that the process and outcome would be very personal.

“It comes down to what would I hang in my own house?” said Gardocki. “What would I collect or what would I acquire to own and want to live with personally and always see every morning or every night? And that’s how I pick.”

Moving around the packed walls of the gallery, Gardocki points out some highlights among this year’s crop. The grinning monster portraits are by Jorge Dos Diablos from Guadalajara, Mexico, who contributed concept art to the 2019 film “It Chapter Two.” The faces are warped, horned and damaged, but still strangely cute. They are clearly children and retain an air of determined innocence, not seeming to care whether they were born as monsters or were made that way.

Adam Maron’s sculptures directly reference a specific North Carolina folk art tradition of utilitarian but busily-ornamented earthenware jugs, with a west coast twist. The back of the jugs are cut away and the interior space is filled with a miniature tableau.

Maron’s piece, “The Wrecking Yard,” forms a diorama of one of the thousand rusty industrial parks scattered across the southland, while “The Butcher Shop” recreates a hundred-year-old photograph of immigrant twins in their place of business.

Graffiti artist, Wizard Skull, exemplified lowbrow’s appropriation of pop culture iconography. Each square canvas depicts a scene from “The Simpsons” in spot-on recreations of the Simpson family home. The color and design of the walls and furniture are identical to the original animation, but the characters are all wrong. Bart’s and Homer’s outlines undulate liquidly, making it difficult to focus on them even as they’re instantly recognizable.

Two of the more visceral pieces came from someone whose work caught Gardocki’s eye at a show at Shulamit Nazarian Gallery in Hollywood last year. Nathan Margoni is one of about a dozen artists whom Gardocki personally invited to contribute work to this show along with the open submissions.

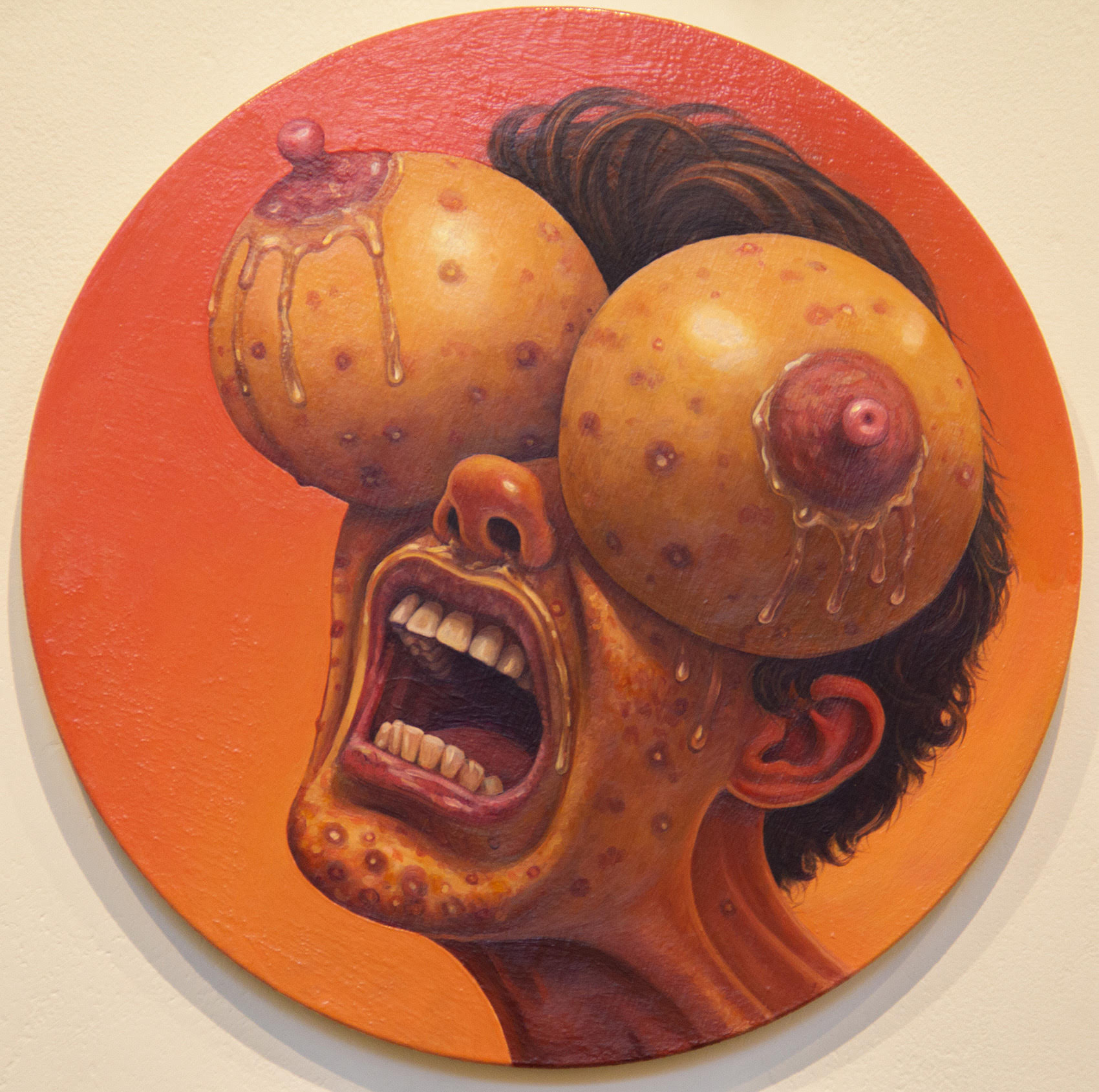

“Did I know I was going to end up with boob eyes? No,” Gardocki said.

Margoni’s “Boob Boy” portraits play out the artist’s continued confrontation with puberty and bodily disgust. The hyper-expressive faces of the teenage boys are dominated by taut, overinflated breasts where their eyes should be. Abundant acne covers their skin.

The “Boob Boy” teenagers seem to exist in a state of unbridled emotion, but not in reaction to the aberrant growth from their eyes. They take the breasts that monopolize their view as a given, at the same time they are overwhelmed by the emotions that well up from within them.

The term “lowbrow” attached itself to the burgeoning movement with the publication of the book “The Lowbrow Art of Robert Williams” in 1981. Williams remains a pillar of the Lowbrow art world today through both his prolific body of work and Juxtapoz magazine, which he co-founded. When Juxtapoz began in 1994, it spread the message of lowbrow across the country.

“I think Juxtapoz helped a lot with getting the work broadcast in its pages, when a lot of people weren’t seeing that work,” said Gardocki. “Once Juxtapoz started to get into those bookstores in the Midwest and the south and that’s where people started to pick up on it. Kids were looking at it, going ‘oh this is work I’m into, I’m not necessarily into what art school might teach.’”

As the movement grew it moved a little closer to the mainstream art world it once rejected. The name “pop surrealism” emerged as a designation for newer artists inspired by lowbrow, but who might have held onto some of the aesthetic traditions they learned in art school or featured fewer copyrighted characters in their weird designs. However, the terms are largely interchangeable.

“It’s been called Lowbrow Art and Pop Surrealism and a bunch of different names, but it’s a feral art,” said Williams in the 2015 short documentary “Slang Aesthetics,” “It’s an art that raised itself in the wilderness.”

Kenny Scharf is another prominent artist in the movement who originated the name pop surrealism. He used it to connect the origins of his ideas with the established surrealist movement.

“Surrealism is about the unconscious and I feel my work is about the unconscious,” said Scharf in the contemporary art magazine Wide Walls. “The images come from the unconscious except that my unconscious is filled with pop imagery. My unconscious is pop, therefore the art would be pop surrealism.”

Lowbrow is entering its fourth decade as a recognized, if nebulous, art movement. As a style that is in part defined by and derived from the popular culture around it, lowbrow’s references are in constant flux.

“Things come and go, so people are over things really quick,” said Gardocki. “There are cyclical things like fashion. It’s the same thing with art. People go through different cycles of what’s ‘of the moment.’ What I was looking at in the early 90s is now cool again, for whatever reason.”

The growth of social media, especially the more image-oriented platforms like Instagram and Tumblr, has proved invaluable for emerging artists to share their work without the gatekeeping of galleries. And, like Juxtapoz magazine, they have exposed that art to wide new audiences. However, for an artistic style that variously relies on novelty, shock and reflecting the images of the world around it, the constant drip of social media content is a double-edged sword.

“It’s hard to push the boundaries now with Instagram,” said Gardocki. “We used to be really good at showing work that was definitely on the outside and deviant and obscure and people that had weird fetishes. But now everything’s out there; nothing is weird anymore.”

Perhaps the shock value of a tree made of lungs or a nude caricature of a politician has been diluted by a couple decades of social media and cable TV, but the march of culture continues even if people are jaded to it. Gardocki sees his role as curator of La Luz de Jesus — especially of the “Everything But The Kitchen Sync” shows — as an opportunity to survey the lowbrow world as it is and add to its momentum.

“It’s a giant community so there’s a lot of work to show,” Gardocki said, “Three-quarters of the people in this show might not submit next year so we’ll have a totally different show.”

- Congressman Schiff promotes $3 trillion ‘HEROES Act’ at virtual town hall - May 27, 2020

- ‘Pain in the ass’: PCC exasperated by federal stimulus rules - April 29, 2020

- PCC’s dash to catch up to COVID-19 - March 25, 2020